It was hard to feel sympathy for Richard Branson, however cruelly Irma had treated him.

The latest alphabetized hurricane had been dominating the news for days now and some of its statistics were stunning, easily qualifying Irma as the most powerful Atlantic storm in recorded history. Sustained winds of more than 185mph meant Irma, according to meteorologists, would have generated over seven trillion watts of power by the time she was done. More than double the impact wreaked by all the bombs deployed in WW2.

Most of the storm’s US biased news coverage had centred on either the approaching threat to Florida, whose 6.5 million residents had been advised to evacuate, or on Washington’s rapidly growing projection that the total clear up bill would exceed $50 billion. Despite this, Irma barely seemed to have registered on the President’s overactive tweet radar. Presumably in The Donald’s opinion it was just a bit of weather, and certainly nothing whatsoever to do with non-existent climate change.

Yet, largely ignored, the heart of the storm had already ravaged The Leeward Islands. The number of people confirmed or feared dead was steadily rising, with more than 60% of the residents on some islands declared homeless. A true humanitarian disaster, Stuart reflected, yet CNN remained fixated on the threat to wealthy Floridian’s condominiums, while an even more parochial BBC seemed to regard the catastrophic damage to Branson’s mansion, on Necker Island, as the key news item.

The bearded billionaire and his domestic staff (an observation that made him sound even more like a plantation owner) were safely holed up in his extensive wine cellar, in communication by satellite phone, but with pretty much everything above ground destroyed. While undoubtedly a personal disaster for Sir Richard, Stuart felt annoyed how little attention, relatively, was being paid to those locals more fatally impacted, less able to recover. How many on Barbuda, closest to Irma’s eye, had a wine cellar they could shelter in or, more pertinently, a $5 billion dollar fortune to rebuild their homes?

Stuart had always regarded himself, though he guessed everybody did, as devoid of bigotry. Yet it would be wrong not to concede that at least part of his anger over this wall to wall, non-stop Necker nonsense could be attributed to the one long held, deep rooted prejudice he couldn’t deny. He was an unashamed, unreconstructed toffist. Suspicious of anyone with a public-school accent.

Its roots were Pavlovian, his high school days in Cambridge having taught Stuart to despise the condescending attitudes, typically voiced in Etonian tones, that so many of its university students showed towards the townspeople. Every time they ventured outside their rarefied dorms and cloisters, it had seemed, displays of assumed, inherited superiority deepened this class centred chasm. Town vs Gown hadn’t proven the myth he had once assumed it was, rather a very real, very unpleasant problem. Thankfully his own student days in Sheffield helped Stuart realise this was a largely Oxbridgian phenomenon, but he had still carried that same conditioned sense of intolerance (of pompous twats) throughout his life.

There was a growing focus these days, rightly, on smashing the glass ceiling, allowing more women to achieve their full business potential, yet insufficient attention was still paid, Stuart felt, to an equally pernicious workplace issue. How many of the senior executives in our purportedly egalitarian FTSE 100 companies boasted Oxford or Cambridge as their alma mater? Too bloody many was the answer.

While Stuart allowed exceptions to his prejudicial rule (who didn’t love Stephen Fry?) he had never found it in his heart to excuse Branson. How could you ever buy a genuine, rags to riches back story for a self-made entrepreneur if their grandfather was a privy councillor, glorifying under the title of The Right Honourable Sir George Arthur Harwin Branson? And just how many fledgling businesses would have survived an early £70,000 fine, and likely imprisonment, for illegally evading purchase tax, without parents like Richard’s who had been able to re-mortgage their home and bail him out?

Stuart’s socialist credentials may have become blurred, without doubt more conflicted, over the years, but this was one working-class chip (quite possibly a whole bag) that had never entirely fallen from his shoulder. Maybe this also explained why, however comfortably middle class he had undeniably become, he still preferred his lyrical diet to come with a healthy helping of left leaning, socially conscious bite. This reflection must have subconsciously bled into his latest Spotify selection, as for today’s one-month on, pre-‘Challenge’ soundtrack he found himself listening to 10,000 Maniacs’ third album ‘In My Tribe’.

Natalie Merchant possessed one of Stuart’s all-time favourite voices (another obvious list category). Her singing, often articulated at the edge of audibility, required a real effort to decipher the words, but with persistence rewarded by poetic story telling lyrics, best delivered angrily, aiming to right perceived wrongs. A theory supported right now by ‘Don’t Talk’s pointed request for truth to prevail over lies. There was a real beauty to the strange timbre of Natalie’s vocals, it seemed to Stuart, one felt as much as heard, a sort of unknowable earth mother tone that had always appeared to be as much of a mystery to her as to the listener.

“Can’t see what all the fuss is about,” Anne always reckoned. “Sounds like Stevie Nicks to me.” There might be a passing resemblance, Stuart had to concede, but it was no real contest, Nicks was no maverick.

Culturally Stuart delighted in dissonance, things that should conflict yet somehow, surprisingly, worked together to create a better whole. David Lynch was his ultimate dissonant hero, with Twin Peaks’ small-town murder mystery cloaking the blackest of psychological traumas, but 10,000 Maniacs’ debut single ‘My Mother the War’ (with the equally weird and wonderful ‘Planned Obsolescence’ on its B-side) had always, to his ears, been a prime aural example of the art.

He knew Charlie, and particularly Ed, would likely denounce such observations as pretentious (Morley like) bollocks. Admittedly a charge hard to refute. They had probably also moaned about, “twee folk rock,” back in 1985, after seeing the band together at the Hammersmith Clarendon (sadly now demolished), but if so, Stuart was confident he would have counterargued, long into the night, about the sheer perfection of the encore they had just witnessed. Introed by an acapella rendition of ‘He’s 1A in the Army’ the band kicked into ‘My Mother the War’ and the following four minutes had stayed with Stuart ever since. At its gloriously undecipherable best, Merchant’s singing counterpointed the post-punk disharmony of the music with the howling guitars in the instrumental breaks perfectly underscoring Natalie’s uncoordinated, whirling dervish dancing. Her long hair and long skirt appeared to take on lives of their own. There was still YouTube footage of this online, from the Newcastle date on the same tour, but it never quite matched Stuart’s recollection.

At this juncture, a dash of personal dissonance distracted Stuart further, prompting him to think of his own mother, to wonder what she had done in the war? Born in 1927 she would have been just twelve at the outbreak of WW2, eighteen by the time it ended. As he had reflected last month, as ‘Challenge 69’s first clue was released, she had left school at fourteen, but what had happened then? He knew his dad, too young to enlist, had been categorised as an essential farm worker during the conflict, but he was a whole lot sketchier on his mum’s war effort. Sadly, she had died (under similar ‘Ocean Spray’ circumstances to James’ mother) before Stuart had been either old enough, or sufficiently mature, to ask.

He had a vague memory of being told she had to travel twenty miles or so, by bus, to work at a ‘munitions factory in Letchworth Garden City. A quick internet trawl revealed a company in the town called Kryn & Lahy, set up by a Belgian diamond merchant after he had fled WW1, which by the late 1930s had employed over seven hundred people, many of them fellow refugees from his homeland. The firm specialised in the manufacture of aircraft supplies, which had to be a euphemism for weaponry if ever Stuart had heard one. Had that been his mum’s war then, building bombs with Belgians?

By the ‘60s she had been a housewife, looking after Stuart and his brother, a seemingly ubiquitous role for women in their rural, working-class community. His dad, meanwhile, that agricultural job made redundant by mechanisation, was working shifts at a local factory. Only looking back now did Stuart appreciate how poor they must have been in pure monetary terms, though with no comparator it had never seemed that way at the time. Having recently read Alan Johnson’s haunting memoirs of growing up in substandard, inner city, local authority slum housing it was clear their own village council house had been a much softer option, but nonetheless life must have been a struggle for his parents. He regretted never having had the opportunity to tell them, with his own wisdom of age, how much he appreciated the sacrifices they obviously made to keep this state as well hidden from him as it was.

Stuart often teased Anne, unfairly and largely inaccurately, that coming from a more privileged middle-class background she could never understand true poverty the way he did. His primary justification for this claim, which Anne chided him, “has scarred you for life,” centred around the single Mars Bar treat his dad brought home each Friday payday. It was only years later, Stuart would explain, that he realised not every family cut their confectionary into four equal, budget constrained segments. It told you everything you needed to know about Stuart’s childhood though, the enormous unpayable debt he would always owe, that his and his brother’s portions had been noticeably bigger than a quarter, and always included the end section, guaranteeing them extra chocolate.

The plaintive strings of ‘Verdi Cries’ returned Stuart from this reverie, its words bringing ‘In My Tribe’ to a close with a final battle call, appropriately heralding the ‘Challenge’ ahead. He had risen early, especially for a Sunday, conscious from the moment he woke that today would bring the competition’s next deadline. With time to kill before he could find out what 10am would unveil though, Stuart tried to pass some of it by watching ‘Andrew Marr’.

More Brexit unsurprisingly, but also a rare sighting these days of Tony Blair. It seemed so long ago now, far more than the actual span of twenty years, since they had believed ‘D:Ream’s anthemic claim that a brighter day had dawned as their song accompanied New Labour’s sweep to power. A moderate left of centre Government offering pragmatic socialism, committed to greater equality but arguing this was best achieved via a society that worked with business, rather than operating in ideological conflict. From the evidence of today’s interview Blair’s tune hadn’t much changed, and nor in truth had Stuart’s views, there was barely a word he disagreed with. Just how had pragmatism fallen so out of favour, he wondered, and politics become so polarised? And was it right that everybody, apparently, had stopped listening to a man once hailed as a visionary over one dodgy dossier decision?

Enough of the Iraq War though, never an argument you were likely to win, and time to switch off Brexit (if only that were possible!). There were now just thirty minutes left before today’s ‘Challenge’ deadline. It had proven a long wait since Stuart had typed VOLTAIRE, pressed Enter, and received in return an immediate if largely uninformative message:

There had been no acknowledgement made, or explanation given, of the worrying absence of ‘Challenge’ number one, but Stuart had at least been relieved that this didn’t appear to have tripped him up. The website didn’t provide its ‘Challengers’ (as he now thought of himself) with any opportunity to communicate directly with the somewhat nebulous ‘Challenge 69’, and despite having checked every few days since there was still no wider online presence through which to gather any additional information.

The only active part of the site, if you logged off and on again, was a simple count, in the top righthand corner of the screen (where the registration numbers had previously sat), which updated the number of people who had passed the latest ‘Challenge’. When Stuart first realised this, at around 10.30am on that first day, it had simply read:

He had obviously been cryptically quick off the mark. Having submitted his answer at just after ten-past ten would, most likely, have put Stuart somewhere close to the front of that initial count. If nothing else, it seemed, you could at least follow how many of the 23,484 ring fenced registrants had passed the test and track the rate at which they were achieving that status. Progress had been slow at first, allowing Stuart to bask in a small glow of pride at his relative crossword competency, but it had soon become clear he wasn’t the only one taking ‘Challenge 69’ seriously. By around 6pm, as he and Anne left for their regular Friday evening pub outing, the count had already risen to 1814/7800.

Anne’s only comment, “who’d have thought there were so many bored people?” had temporarily punctured Stuart’s enthusiasm, but it had proven no more than a slow puncture, easily patched. He was officially hooked.

In the end it had taken just over two days for this success counter to reach its limit (7800/7800), consigning the remaining 15,000 plus entrants to the losers’ lot, presumably now permanently locked out from the ‘Challenge 69’ site. As Stuart had quickly learned to expect, there had been no fanfare as this total was reached. Any subsequent logons to the site simply met with a repeat of the same static message, instructing those ‘Challengers’ still alive to log back in at the same time next month.

It felt odd to be part of some exclusive club, even odder to have absolutely no idea who your fellow members were, but ultimately Stuart had followed Anne’s advice to, “put your toys back in the box,” and had busied himself with other stuff. Albeit he had kept half an eye on the calendar as it counted down towards 10th September.

He decided he could kill the final twenty minutes of his long month’s wait by refining the ‘best female voice’ list that Natalie Merchant had prompted him to start mulling over earlier, though he slightly agonised whether, like the Oscars, he could nowadays be criticised as being genderist for keeping women separate:

5) Liz Frazer – Stuart could take or leave a lot of the Cocteau Twins, but never failed to be both startled and entranced by This Mortal Coil’s ‘Song to the Siren’ (which on reflection should probably have made his covers list).

4) Aretha Franklin – while he had never been a huge devotee of soul, Aretha’s voice was still as effortlessly essential to this list as Elvis’s would be to a male version. If you needed any convincing, then just watch her steal the ‘Blues Brothers’ film.

3) Lorde – much like Kate Bush had once done, with ‘Wuthering Heights’, it felt like Lorde had discovered a way to reinvent singing on ‘Royals’, and a couple of albums later Stuart still found her voice fascinating.

2) Moira Rankin – bringing an inevitable challenge of who? But His Latest Flame’s ‘Stop the Tide’ was one of Stuart’s perennial favourite lost singles (another list?). Moira had this stunning, country twang voice he never tired of.

1) Natalie Merchant – a deserved ever-present on this list, in Stuart’s opinion (with ‘San Andreas Fault’ his go-to solo track), predictably securing today’s number one spot off the back of his morning’s listening.

Reading back over his final list made Stuart smile, particularly his number two entry as he imagined Ed’s likely response, “why do you always have to be such a pretentious git?” There were some absentees he felt guilty about: Siouxsie, Patti, Sinead, PJ, Amy, and Delores, to name just a few. Equally there were others that caused no such angst. He knew many would argue that if Aretha made the cut, on quality of voice alone, then Whitney Houston should join her. But Stuart knew he would rather stick knitting needles in his eyes (or should that be his ears?) than ever include Whitney and her overinflated syllables on any of his lists.

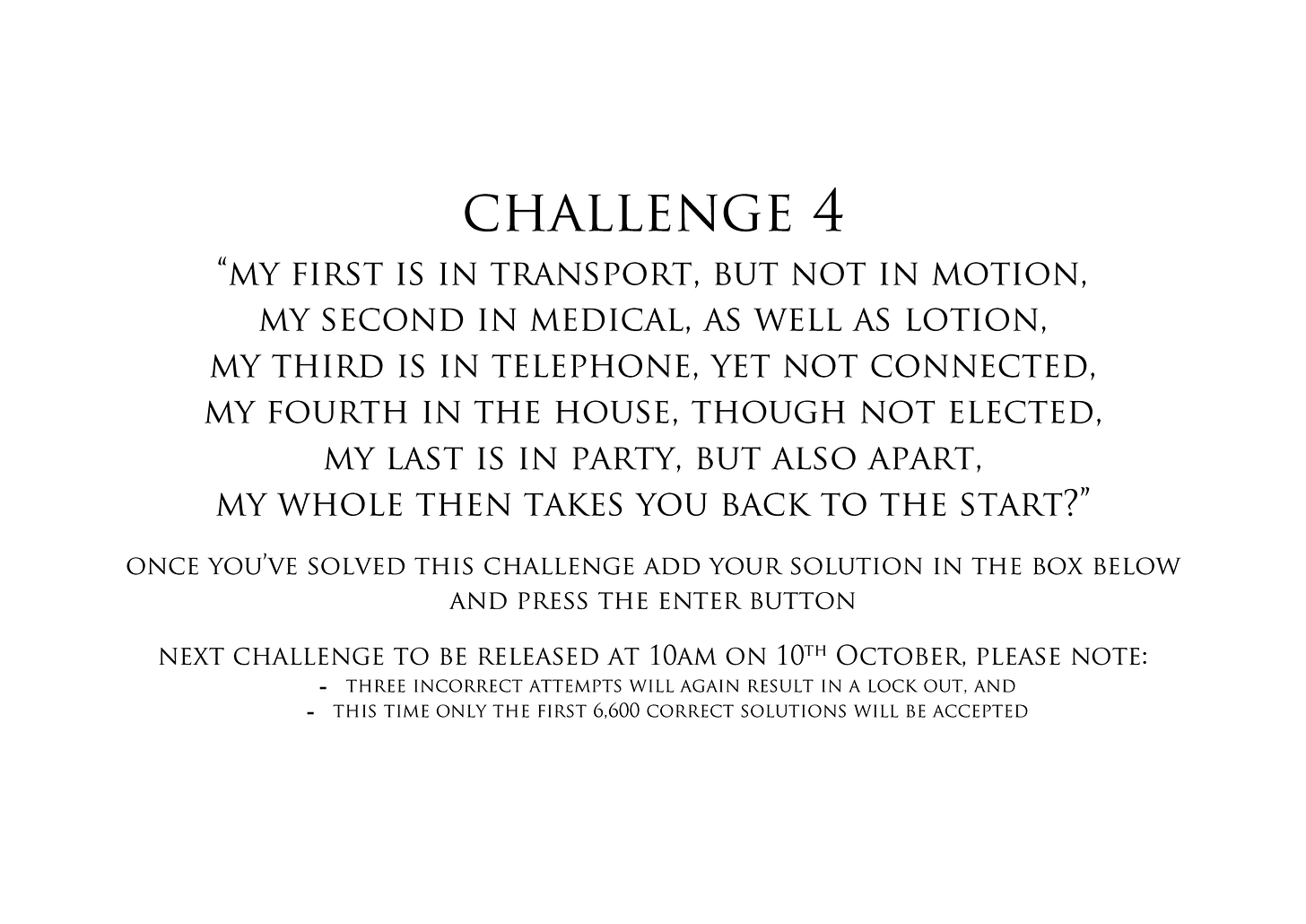

Having risked an abortive logon at 9.58am, trying to get ahead of the game, the following message appeared right on schedule at the top of the hour:

###

(To be continued, at 10am tomorrow. Can you solve ‘Challenge 4’ in the meantime? If you think you have got the answer, then please reply direct to this email post, to keep the ‘challenge’ open for other readers.)